By Nikki Weiss, PhD, Center for Public Health Systems, University of Minnesota School of Public Health

As a qualitative researcher, I spend my time working with ideas and narratives, and every day I witness how these data not only enrich quantitative data but can also stand alone to paint a picture of our public health landscape. I believe that qualitative data are underutilized in public health, and this blog post will describe the basics of qual data and how we can use this type of data to become better leaders in both the public health and clinical health spheres.

Basics of Qualitative Data

First, let’s define qualitative and quantitative data.

Qualitative data: story- and narrative-based data

Quantitative data: numbers-based data usually analyzed via statistical analyses

Each type has its pros and cons: for example, qualitative data can enrich quantitative data and shed light on complex realities that quant data are not able to characterize, though qual data usually aren’t as easily replicable. Using them together can strengthen research by way of triangulation, which is using two different methods to see where results align or overlap.

Collecting Qualitative Data

But how does one collect qual data? There are multiple methods, a few of which I’ll describe here.

- Interviews are when the researcher asks questions of one or two participants, and interviews can be structured (every participant receives the exact same questions), semi-structured (an interview guide is used but the interviewer can add questions in response to noteworthy responses of the participant to follow up on a topic), or unstructured (no interview guide is used).

- Focus groups and listening sessions are similar in that questions are asked but of a group, usually in a semi-structured format (listening sessions tend to have larger numbers of participants than do focus groups).

- Ethnographies are anthropological investigations in which participant observation is the main method (i.e. shadowing the participant as they go about their everyday life).

The data that are collected from these types of methodologies are either transcripts (verbatim written records of what has been said, usually for interviews/focus groups/listening sessions) or notes (for ethnographies in particular but often used as a backup for if recording fails in interviews/focus groups/listening sessions).

Content Analysis

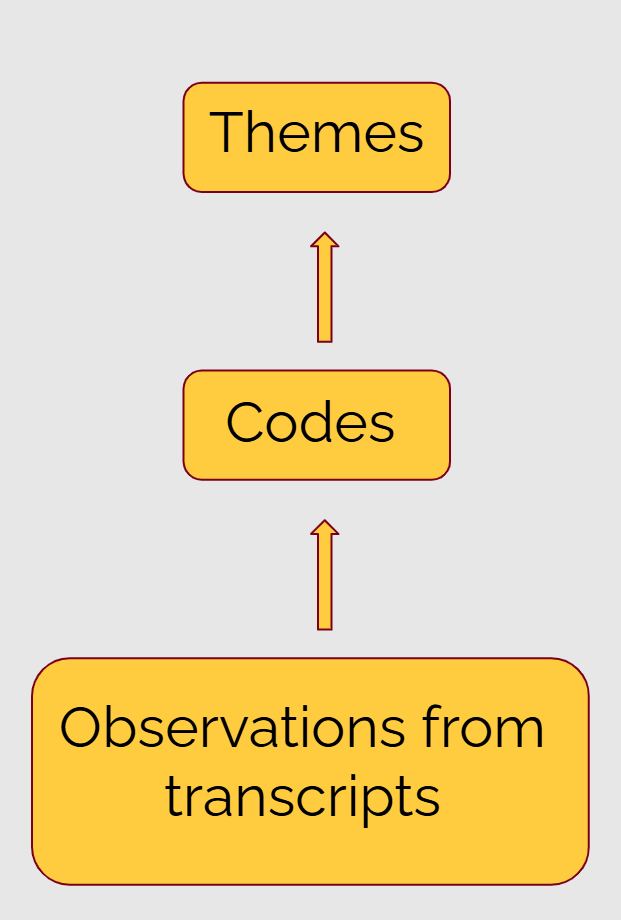

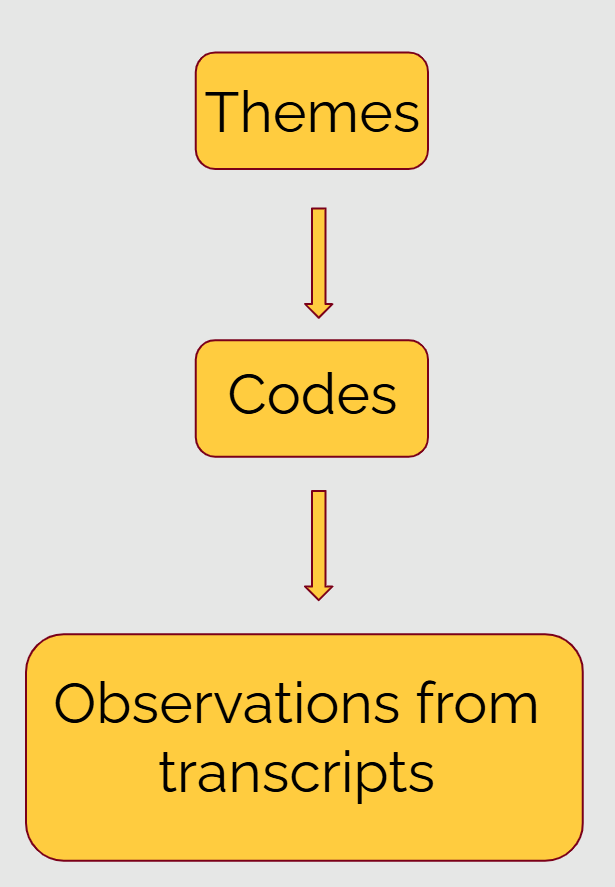

Once the transcripts are ready, a common next step is to examine them using content analysis, which is a process that involves assigning labels (“codes”) to ideas in these transcripts. Content analysis can be inductive (Figure 1), in which codes are derived from the data and are created as the coder moves through the transcript (“bottom-up” or specific to general), or deductive (Figure 2), in which codes are created before the coding process begins based on themes that are expected to appear (“top-down” or general to specific). In addition, inductive and deductive approaches can be fused for a more iterative approach to coding.

Figure 1. Inductive codes are built “up” from observations within transcripts to codes and then themes.

Figure 2. Deductive codes are created from themes that researchers expect to appear in participants’ responses. These codes are then applied to the transcripts.

Using Qualitative Data

Now that we have a basic understanding of qualitative research and how to analyze qual data, we can discuss how to utilize qual approaches to become better leaders. First, qualitative data can help us understand workforce issues as well as how to mitigate them. For example, high turnover could be examined using exit interviews, and content analysis could be performed on the transcripts of those interviews. But if recruitment is a challenge, then focus groups of recent grads could be held to get a better understanding of why folks aren’t applying to job postings. Second, qualitative research aligns with ideas of adaptive leadership in terms of listening and trying to determine root causes of issues to address. This type of research helps us understand experiences that aren’t necessarily our own, and when we understand them, we can begin to address them.

Conclusion

In summary, qualitative research has unique pros and cons, just as quantitative research does, and both types of research can be used together to complement one another. There’s no one way to collect qualitative data, and there’s no one best way to analyze it either. Once analyzed, qualitative data helps shed light on nuanced experiences that numerical data might not be able to reflect, and these insights help us grow and develop as leaders in public health and clinical health.

To learn more, check out these resources:

- Nikki Weiss’s RVPHLI session

- Qualitative Methods in Public Health Practice (No CE)

- Knowledge, Narratives, and Numbers: Strategic Storytelling as a Foundation toward Transformation (Self Paced-CE)