This post comes from the RVPHTC’s partners at the Center for Public Health Systems, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

By Harshada Karnik, PhD, MS, MPP, Rachel Schulman, MSPH, CPH, and JP Leider, PhD

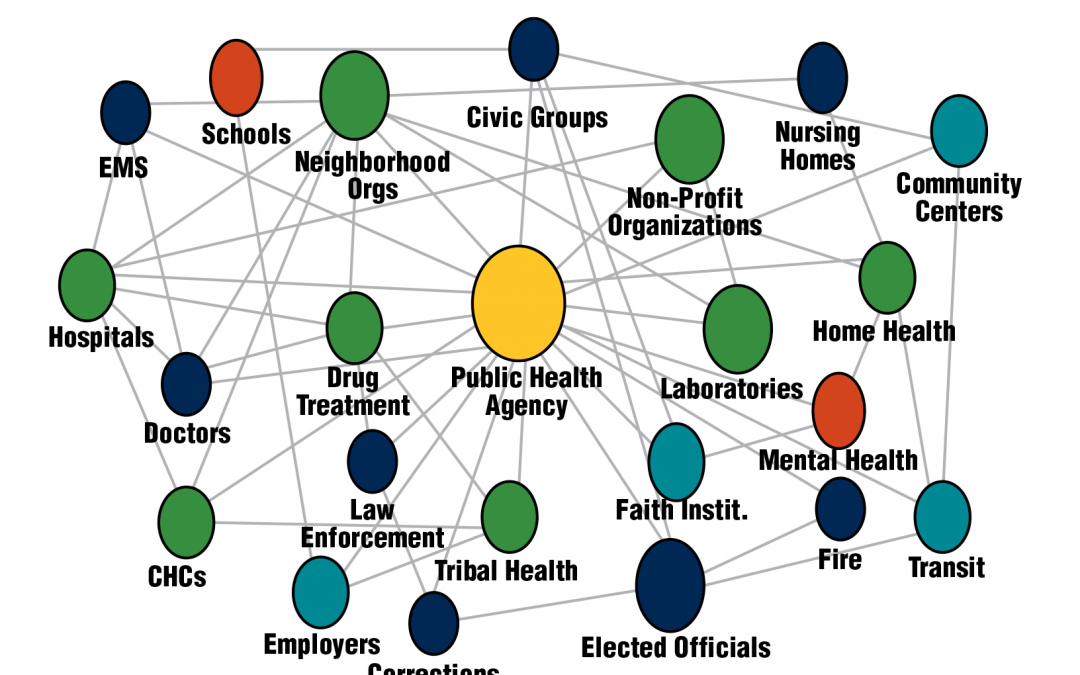

Image Source: CDC Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support, 2021

Popular discourse on health has focused primarily on private healthcare, covering issues such as how difficult it is to see doctors and specialists, how expensive and inefficient it is, and how we can improve these systems. This makes sense given that we spend more than $4 trillion on health in the US, with the vast majority going to personal healthcare. Relatively little of our national conversation on health is about public health, which is right in line with our spending on public health; less than 3% of that spending goes toward governmental public health, i.e public spending through federal, state and local agencies and services provided by them. Public health protections and population-based surveillance represents just 2 or 3 cents of every health dollar in the US. And everything going into that 3% is what we study at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health Center for Public Health Systems (CPHS). We are all about governmental public health.

But what are public health systems more broadly? Public health systems include all public, private, and voluntary entities that contribute to the delivery of essential public health services within a jurisdiction. It is a network of state health agencies (SHAs), local health departments (LHDs), safety net health care providers, public safety organizations, and other community-based organizations that contribute to people’s health and well-being at a societal or collective level. Public health services range from restaurant inspection and vaccine distribution to messaging around cancer prevention.

LHDs are at the center of the public health system. Historically, local health departments emerged to control communicable diseases and provide safety net clinical care in their communities. As the threat of communicable diseases decreased over the last century, LHDs started focusing more on prevention of chronic diseases such as diabetes and offering clinical services particularly in medically underserved communities. The population-based services and monitoring functions for which LHDs were originally responsible took a back seat to medicalization of public health issues. With these historical public health issues viewed as “solved,” federal and state financial support declined, and local agencies have been increasingly left to raise their own funds. The shift toward providing clinical services in healthcare settings further eroded their funding. The gap in the regulatory functions presents an opportunity to reimagine a public health system focused on population-based prevention and inspection/regulation, but extrication from clinical service provision has proved difficult.

In the past decade, outbreaks such as Ebola and H1N1 influenza once again brought the emergency preparedness and disease control and prevention roles of LHDs into focus. And now, of course, COVID-19 response and recovery needs have highlighted both the key role that LHDs play in these critical public health functions and also the challenges they face in doing everything that is needed of them after years of underfunding.

At the recent NASEM Roundtable on the Population Health Workforce, CPHS (and others) discussed the renewed need for academicians and practitioners to identify the key functions that local health agencies play in promoting resilient communities, examining the workforce and resource gaps needed to fulfill these duties, and identifying solutions to create a functional and sustainable public health infrastructure. The work begun in PHSSR fifteen years ago requires reinvestment, as its research agenda has largely languished since publication due to lack of funding. A new agenda is long overdue, as is work in this important space. There is a significant amount of structural variation across health departments — every health agency in the country has a different staffing model, organizational structure, and operating protocols. Therefore, renewing PHSSR will require work on the national level as well as on the state and local levels.

About the Center for Public Health Systems at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health

CPHS is one of the RVPHTC’s technical assistance providers, with a focus on evaluation. At CPHS, our goal is to innovate public health practice through research and evaluation, technical assistance, and workforce assessment to improve health outcomes in Minnesota and the nation. We have two primary aims: the first is to support state and local public health departments around areas of self-identified need through evaluation, workforce assessment and development, cost estimation, and other technical assistance. The second aim is to conduct evidence-based research in the spaces of public health workforce, finance, and systems more broadly to inform policy efforts to understand and strengthen the public health workforce nationwide. By convening and collaborating with public health practitioners, associations, and researchers, we endeavor to unite varied stakeholders in our common mission to improve public health systems in a real and lasting way. Contact us if you would like to talk more about public health systems.

This blog post is also available on JPHMP Direct’s Wide World of Public Health Systems blog.

Interested in learning more about governmental public health? Check out these trainings from the RVPHTC: